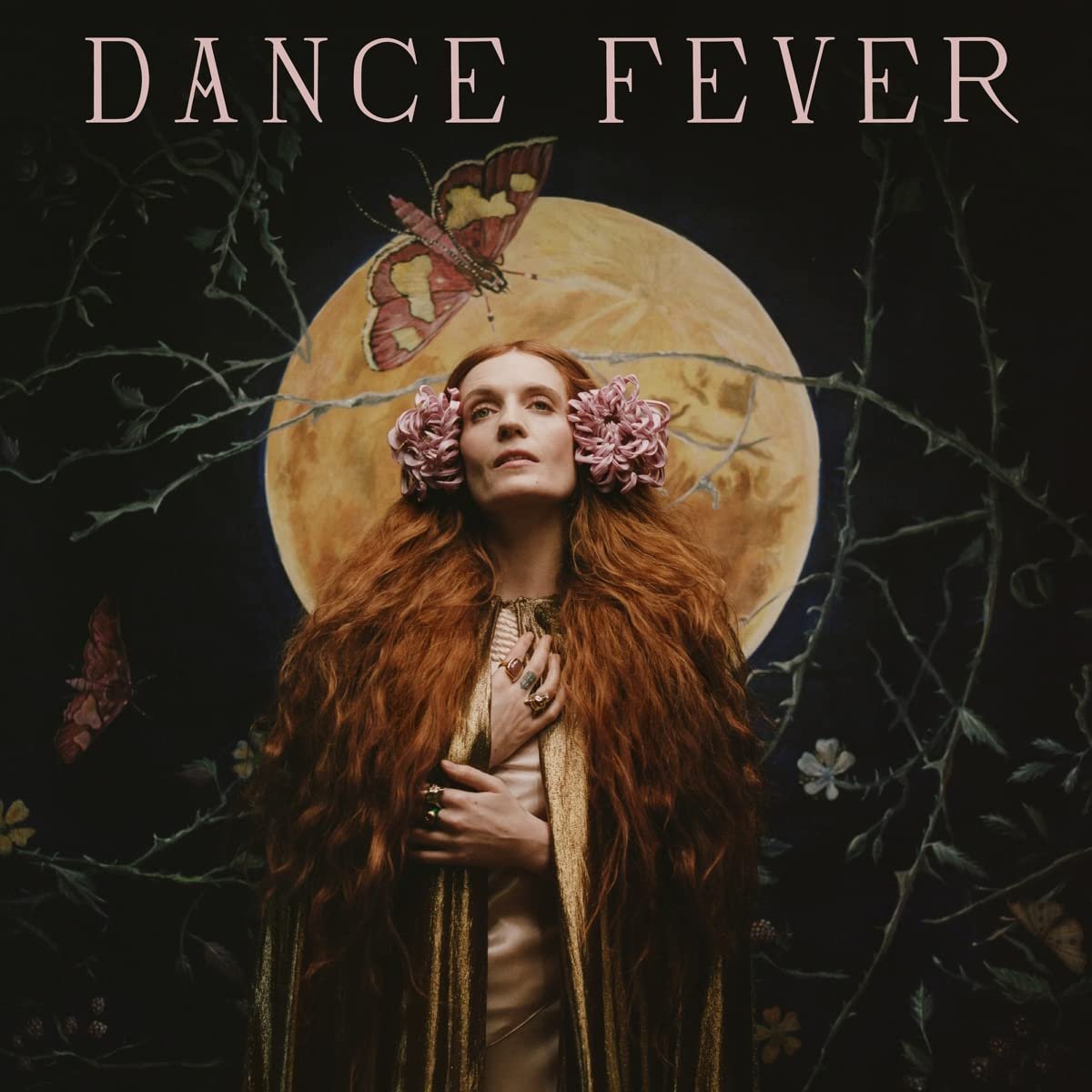

Florence + The Machine: <em>Dance Fever</em>

8.8

GENRE: Rock/Chamber Pop

YEAR OF RELEASE: 2022We can now travel on overbooked flights, rumba lessons are back in my gym, and Coachella is a thing again. There are no more scenarios in which mentioning the pandemic is still an attractive way to start a conversation. But when Florence + The Machine put out “King,” the first single from their fifth record, Dance Fever, they knew the world would want to hear Welsh’s strident voice and goth perspective on isolation. She’s known for her pre-Raphaelite aesthetic, cosmic aura, and cathartic hooks, which now feel more messianic than ever. True, we have begun to look forward to the future, and quarantine memories have begun to fade alongside Dr. Fauci’s appearances on TV. But in order for us to go on with our lives, artists like Florence Welsh have to experience things and document them, write and sing about them, relive them for however long an album promotion and tour take—God willing, they get cured in the process. Appropriately, Dance Fever is the unavoidable result of quarantine loneliness, a mix of self-doubt and self-assurance inspired by folk horrors and bolstered by Welch’s soaring yet soothing voice.

A band with festival designs, the sound of Florence + the Machine has been corporeal since their early days: one way or the other, the band always found ways to materialize Welch’s majestic, bigger-than-life concepts. Their earlier works were absurdly grand, involving you in the position of an onlooker who taps their feet to the music but not too much to avoid missing anything. On Dance Fever, some of the songs get you going. Really dancing. It’s brave music, their most ambitious and incantatory yet. Inspired by an old plague where people danced until they collapsed in ecstasy or died, Dance Fever mingles the phenomenon with current life during the pandemic, juxtaposing euphoric body movements with suppressed boredom and hopelessness. These narrative amalgamations are subtle, so it’s easy to get carried away by the beat and let the poignant plots of the songs slip. Welsh’s lyrics used to be about searching for freedom and enlightenment, the arrangements usually agreeing with her words. On Dance Fever, she cans themes like anxiety and loneliness in airtight melodic structures, sounding realistic and disillusioned, dancing to her possible failures and seeing them as half-victories.

On Lungs, Welsh sang about being goldened by Midas King’s touch on “Rabbit Heart (Raise It Up).” On Dance Fever’s opening track, she is king herself, albeit not for mythic braggadocio. Here, demands her “golden crown of sorrow,” implying that her career as a musician comes at the expense of living through “ordinary” womanhood (“I am no mother/I’m no bride”). The song entertains the difference in genders by diminishing it to nothing, crowning Welsh as king rather than a queen. But even then, it’s hard to tether from preconceived notions of our society. “You say that rock n’ roll is dead/But is that just because it has not been resurrected in your image?” she sings on “Choreomania,” provoking men who still don’t think women can be rockstars. The song has a transfixing mellotron played by the highly-demanded Jack Antonoff, who also co-wrote and co-produced the track that, surprisingly, bears no similarities with Antonoff’s recent productions (Clairo, Lorde, Lana Del Rey). Well, it’s impossible to make Florence + The Machine sound like any other act, thanks to their signature celestial harps, organs, and choirs.

Dance Fever takes Welch’s voice down a few notches and lets the arrangements lead, providing the ebullience that is absent from its predecessor, High as Hope. On the brash “Free,” a tantalizing industrial rock with skittering beats, Welsh talks candidly about her anxiety; “Sometimes I wonder if I should be medicated/If I would feel better just slightly sedated,” she ponders. While the beat is effervescent, the verses capture the rollercoasters of anxiety and its swings, describing a sudden feeling that “picks me up and puts me down/A hundred times a day.” As on many other “lockdown albums,” mental exhaustion is a common thread running through Dance Fever. In “My Love,” Welsh reflects upon being unable to write—a recurrent theme in her discography. “Now I find that when I look down, every page is empty,” she croons over blooming keyboards while the beat ambles steadily.

On “Cassandra,” Welch positions herself as the future-teller from Greek mythology: “I used to see the future and now I see nothin’,” she laments, referencing a song from 2018 in which she pleaded people to stick together—two years before COVID hit. “Made myself mythical, tried to be real/Saw the future,” she bemoans on later track “Daffodil.” All these metalinguistic wails are a result of isolation and agony caused by the free time in the pandemic. Many albums in 2022 come from the same place, but on Dance Fever, Welsh chants her sorrows with serenity, without overloading them with cloy, tying everything together with cohesion, repeating storylines without sounding monotonous. She juxtaposes longing for the pre-pandemic life with realizing she took that life for granted. “I listen to music from 2006 and feel kind of sick,” she croons on one song. “Never really been alive before/I always lived in my head,” she concedes on another.

These assertions, made by Welsh with a diversified yet congruent attitude, are like a glaze on top of her decade-long career with Florence + The Machine. For a band usually ensnared in their own grandiosity, Dance Fever is the first album with a clear sense of purpose and concept, without its subject matter getting lost here and there. There is no lingering fear of being too dramatic or too contrived. Instead, Welsh spends the album tackling things with the kind of honesty that might put her in the wrong light: her privileges and shortcomings as a musician, her recognizing it as a non-conventional profession, her talking about the sorrows of fame without expecting people to feel sorry for her but causing them to do so anyway, her persuading people to join her in the awkward dancing as if no one’s looking. For Welch, Dance Fever is the much-needed equilibrium after the blandness of High as Hope, the overarching ambition of How Big, How Blue, and the blaring self-help of Ceremonials.

Listen to Dance Fever :