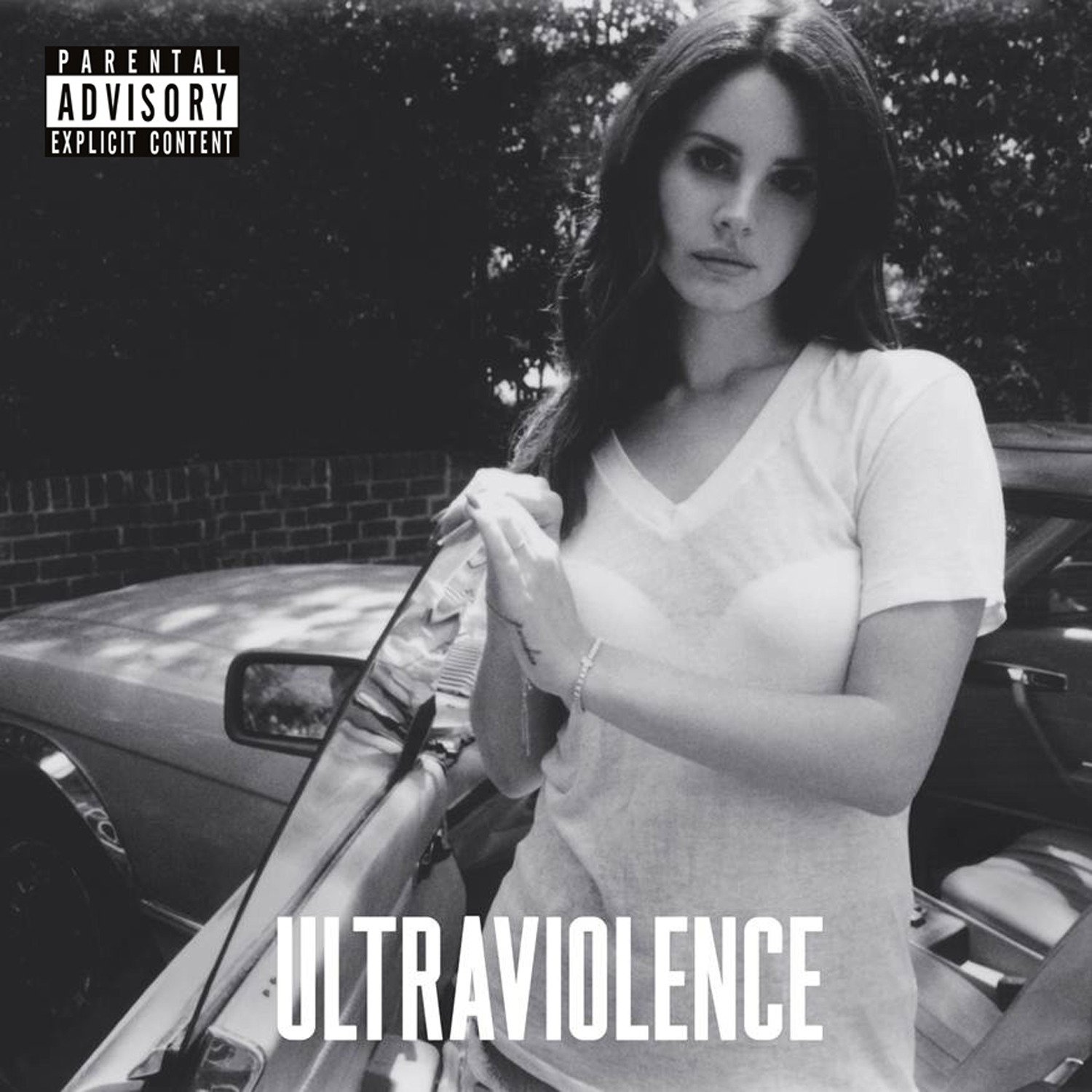

Lana Del Rey: <em>Ultraviolence</em>

8.0

GENRE: Alternative

YEAR OF RELEASE: 2014By the time the world understood Lana Del Rey was more than gimmicky productions, the singer had already crossed the bridge. With a cigarette in hand, she sat there and waited for her critics to catch up. It must have been lonely—feeling underestimated and better understood by an electric guitar in the studio. But out of her solitude came her second record, Ultraviolence, on which the singer plumbed new depths into her psyche and veered away from the glamorous pop of her debut album, Born to Die. With alleged inspirations varying from the Eagles and the Beach Boys to Burgess, Del Rey dropped a disguised avant-garde statement for the ages, comprised of psychedelic rock, blues and soft rock arranged tracks. The album went against everything on the radio in 2014—her game was the only one she would play.

Ultraviolence shows that, out of all the hippie nostalgists to come out of the early 2010s, Del Rey might be the one who most organically incorporates her influences. “Brooklyn Baby” drips with knowing satire of beatnik culture (“Well my boyfriend’s in a band, he plays guitar while I sing Lou Reed“), yet the reverb-heavy guitars and dreamy production make the homage feel earned rather than ironic. On “West Coast,” she channels both Nancy Sinatra’s sultry delivery and the Doors’ psychedelic arrangements, creating something that sounds vintage yet oddly futuristic to declare her love in the first of what would become a series of love letters to Los Angeles.

The strangely aloof detachment that critics misread on Born to Die, then, becomes Ultraviolence’s greatest strength. Producer Dan Auerbach brings his Black Keys sensibilities to tracks like “Cruel World” and “Money Power Glory,” where fuzzy guitars and ethereal vocals create a narcotic haze that perfectly matches Del Rey’s themes of toxic love and American decay. “He hit me and it felt like a kiss,” she sings on the highly criticized title track, referencing the Crystals’ controversial 1962 single while exploring the darker corners of romantic obsession. Del Rey had to explain herself quite a few times over where she stands on feminism because such lyrics. But is she really glorifying abuse here or simply playing into the American psyche that’s infiltrated by the harsh reality of a patriarchal society? Are there not women who fall victim to violent love? Is it a crime to sing about it?

Del Rey’s voice, often criticized early in her career, reveals new depths here. On “Shades of Cool,” she moves from breathy verses to a stunning falsetto chorus that pierces through the James Bond-worthy arrangement. “Pretty When You Cry” finds her deliberately straining her voice to its breaking point, the imperfections serving the song’s raw emotional core. These weren’t the choices of someone chasing radio play, really—they were artistic statements from someone who’d found her true voice.

But the album’s genius actually lies in how it transforms vintage American sounds into something deeply contemporary, even with crying distorted guitars. “Fucked My Way Up to the Top” might sound like a torch song from another era, but its frank examination of power dynamics in the entertainment industry feels startlingly relevant (and a very direct jab at Lorde, some say). “Old Money” wraps class commentary in strings and piano that recall Hollywood’s golden age, creating a critique of wealth that’s both timeless and timely.

Despite its brilliance, Ultraviolence—polarizing to some—can feel like a somber, monotone chapter in a larger story still unfolding. It was an exciting moment then, one that made us feel like the next record by Del Rey would be something to look out for. Consequently, Ultraviolence stands as proof that Del Rey’s initial critical drubbing said more about music journalism’s blind spots than her artistry. The mid-century ballads spiked with blues-rock weren’t just a shocking accomplishment for an artist once dismissed as an industry plant: They became a blueprint for how to alchemize influence into innovation. They whimper and howl, soothe and taunt, hypnotize and thrill, but most importantly, they stand entirely apart from the maximalist pop of 2014. Ten years later, as artists from Taylor Swift to The Weeknd mine similar territory of American mythology and doomed romance, Ultraviolence feels less like a departure and more like a prophecy.